On a very wet Sunday in February, with Storm Dennis doing his best to ruin the weekend, we were joined by 30 local volunteers in waterproofs and wellies to tackle climate change head on for our tree planting day.

Trees are the lungs of our planet, they absorb carbon, fight flooding, reduce pollution, nurture wildlife and enhance the beautiful English countryside. Since 1987, we have planted over 8,000 trees on the farm and this time, we thought we would ask the local community for their help with our next tree planting effort.

With the support of The Woodland Trust, we were advised to choose trees that suited the wet conditions of the area the trees would be planted in. They suggested hawthorn, crab apple, hazel, goat willow and holly, which will grow to create a wild wood area. We bought the trees from The Woodland Trust, they sell small saplings that are UK sourced and grown to help prevent the spread of trees diseases and pests. By buying trees from The Woodland Trust, it helps support the fantastic work they do in protecting, restoring and creating the UK’s woodlands. To buy your own trees from The Woodland Trust, visit their shop here.

To start the day off, all our volunteers gathered in our grain store and were served delicious tea and coffee from local coffee roastery, No. 13 Coffee. They roast their own beans in nearby Kettering and then serve their coffee from a converted horse box, which is solar powered! Eli Farrington made a wonderful selection of cakes, all using Mellow Yellow Rapeseed Oil. With everyone settled with a hot drink and slice of cake, Duncan explained why planting trees is so important and the correct tree planting technique. Then it was time to head out into the rain. Armed with spades and umbrellas, we handed out the saplings and our trusty volunteers got digging!

By the time all the trees were in the ground, everyone was pretty wet and cold, so we went straight back to the grain store to enjoy another hot drink from No. 13 Coffee and another slice of cake, after all, we had earned it!

The weather didn’t dampen anyone’s spirits and we hope all our volunteers had a nice time. Trees absorb carbon dioxide all their life, but are most efficient during their teenage to middle age years. So for the next few years, these trees will focus on growing and then in about 10 years, will start really making a difference to global atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. Planting trees is a true investment for the future of our planet, so we are incredibly grateful for all our volunteers and the help they provided! If you want to learn more about why planting trees is so important, have a read of this blog post.

If you want to plant your own trees or attend a tree planting day, visit The Woodland Trust’s website.

What is carbon sequestration?

“Carbon sequestration is the long-term removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to be stored in plants, soils, geologic formations or oceans.”

This sentence very simply defines what carbon sequestration is, but I will explain a bit more about what it actually means and how soils and sustainable farming practices can have a major impact on reducing global warming by reducing the carbon dioxide (CO2) levels in the atmosphere.

Soil carbon sequestration is a natural process powered by growing plants, through the process of photosynthesis. Plants photosynthesise with the energy from sunlight, taking CO2 out of the atmosphere and converting this into new plant material, both above and below the soil surface, locking up the carbon and releasing the oxygen back to the atmosphere. The process works in symbiosis with the minerals, water, bacteria, fungi and other organisms in the soil. Plants grow, die and decay, feeding the soil and the life within it. Over the long term, CO2 is removed from the atmosphere, locked into the soil and, stored in the plants. This is carbon sequestration and the soil is known as a carbon sink.

What is soil?

Soils are naturally made up of four different components, a typical soil consists of:

50% Mineral

20-25% Water

20-25% Air

1 to 12% Organic matter

Obviously, the specific percentages will vary from one soil to another and whether or not it is in wet or dry conditions for example. In winter soils will contain more water than in the summer. The organic matter is made up from all the living and dead material: bacteria, plant roots, dead leaf litter and animal manure for example. This organic matter is full of carbon that is locked in the soil. Different soils will have different soil organic matter (SOM) contents and therefore different carbon contents. For example, a sandy soil will have a low SOM of around 1%, where as a peat-based soil will be at the top end, with clay soils somewhere in between.

A bit of soil history

Around 10,000 years ago man evolved from being a hunter gatherer to a farmer as they started growing crops and grazing animals. They managed the soils, changing the natural habitat to one more favourable to their needs. Right from the first farmers, man has not been very successful at looking after our soils. In fact, every empire in human history has eventually failed due to starvation, mainly bought about by soil degradation. From the Roman Empire, to the more recent collapse of the Soviet Union.

President Franklin Roosevelt once stated, “A nation that destroys its soil, destroys itself.” Wise words indeed, based on thousands of years of proof. However, when Roosevelt made this statement, he was probably thinking of the dust bowls in the mid-west of the American prairies and the loss of the natural habitat caused by farmers ploughing up their land to grow crops. He was very aware of the nutritious soil literally being blown away and was no doubt aware that unless farming practices changed, in time this land would not be able to produce food. But he was probably not aware that the general degradation of the soil was also releasing many thousands of tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere, adding to what we know today as Global Warming.

Traditionally farmers plough the land, a process to turn the soil over to create good conditions in which to plant the following crop or pasture. However, when the soil is moved intensely as it is in ploughing, the carbon that is locked into that soil is suddenly exposed to our oxygen-rich atmosphere, resulting in the carbon combining with the oxygen to make carbon dioxide, which is released into the atmosphere. At this point the soil changes from being a carbon sink (removing CO2 from the atmosphere) to become a carbon source (releasing CO2 into the atmosphere). Over a few short decades, soils will lose their carbon content and thus reduce the soil organic matter, not only releasing global warming CO2, but also making the soil less nutritious and resilient to extreme weather conditions, which is not good for the farmer.

How are we improving our soils on Bottom Farm?

There is a better way we can grow our crops and graze our animals, using sustainable practises carried out by the likes of LEAF farmers (Linking Environment And Farming). These sustainable farming practises have three crucial but simple requirements to make soils healthy:

– Reduce soil disturbance from intensive cultivation and ploughing

– Keep something growing in the soil all year

– Vary the crops and livestock grown on the soil

By reducing cultivation, and especially ploughing of the soil, the loss of CO2 is greatly reduced. By keeping something growing in the soil as long as possible, not only are the plants utilising the power of the sun, photosynthesising and actively absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere, but the roots are feeding all the microbes in the soil to keep a healthy biodiversity. Finally, by varying the crops and livestock grown on the soil, the farmer better mimics what would happen in nature keeping the soil in good health.

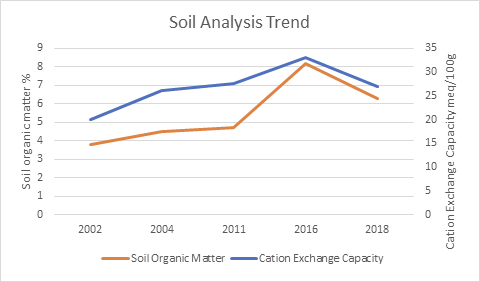

If farmers follow these simple principles, they can again turn the soil back into a carbon sink, sequestering carbon in the soil and increasing the soil organic matter. I have done this on our farm over the last two decades and on one field which I have been monitoring, I have increased the soil organic matter from 3.8% to 6.3% between 2002 and 2016. To put this into context, if every farmer around the world practiced sustainable soil principles, our soils have the ability to remove 1 trillion tonnes of CO2 from the atmosphere, taking us back to pre-industrial levels. So, the prize is extremely big and very worthwhile aiming for.

I think I might be a Tree Hugger.

I have always appreciated the beauty of and adaptability of trees, whether this be an individual tree impressively showing its unique beauty in the open countryside or adding a warmth of texture to the architectural lines of an urban setting. Together trees make the copses and woodlands that characterise our British landscape, creating our ‘green and pleasant land’. 13% of Britain is covered in woodland, up from just 5% at the beginning of the last century when the Forestry Commission was established. Britain also has an exceptional number of ancient trees compared to the rest of Europe, these trees are a living history, wrapped up with mythology and traditions stretching back thousands of years. Trees provide a home for other forms of wildlife from lichens and fungi, to insects, birds and small mammals. They are also a valuable source of food for wildlife and humans alike, as well as timber having many uses; from being a fuel or an important raw material to build everything from ships and buildings, to fine furniture to the more mundane but essential: paper for toilet rolls.

As a young boy I can just about remember the grand knarled Elm trees around the farm, most of which succumbed to the devastating Dutch Elm Disease which just about wiped this species out. Luckily, a few Elms survived which are resistant to the disease, but this is now a rare sight. From the 1980s, farmers started to be encouraged by government policy to plant trees on their farms to replace the former trees that had been lost over the years from Dutch Elm disease and from those pulled out following the second World War, where government policy had encouraged farmers to grow more food ensuring Britain was never held hostage to food shortages again.

Over the years, my father and I have planted well over 8,000 trees on our farm. Father started this in 1987, establishing two small copses of native deciduous hardwoods and fruiting trees in awkward field corners. Now some thirty years later, these trees have added real beauty to the landscape, as well as providing habitat and food for wildlife. From autumn 1989, as soon as I left school, I planted my first trees on the farm and spent many subsequent winters with a spade and flask of tea planting trees and hedges around the farm. Over the years, these have needed weeding, tending and replacing ones that either died in summer droughts, or were eaten by Muntjac and hares. But now as they grow and mature, I find real pleasure in seeing them evolve, becoming part of the landscape.

When I first started planting trees and hedges on the farm, my motivation was to improve the visual character of the farm, by creating a network of small copses linked by hedgerows next to water courses or across fields. For example, I created a beetle bank across our largest field and planted it with a mixture of tree and hedge plants. This created a wildlife corridor from an old hedge at one end to a small copse at the other. Over the years it has provided habitat for Grey Partridge and other farmland birds, as well as small mammals and insects, including of course beetles. It is visible from a nearby bridleway, providing an interesting focal point on the horizon.

In addition to the visual and wildlife benefits, many of the trees we have planted such as English Oak, will in time be a source of quality timber, however this will be long after I have gone. But I have also planted a couple of areas of Poplar trees purely for their timber around twenty years ago. This is a quick growing hardwood which takes around twenty five years to mature. So these will soon be ready to cut down to make pallets or furniture frames, following which we will replant the areas with more trees in their place to start the cycle over again.

Since I started planting trees on our farm as a way of improving our own little part of the countryside, the appreciation of trees in the wider world to reduce flooding and soil erosion has become more apparent. However, the biggest change over the last decade has been the wider realisation of the ability of trees to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and the sense of despair at the continued global deforestation, especially in the Amazon basin, often thought of as the planet’s lungs. Admittedly the 8,000 trees we have planted is not going to make up for vast tracts of lost rainforest, but every little bit genuinely helps.

Trees absorb carbon dioxide all their lives, but are most efficient during their teenage to middle age years. Therefore, the trees we planted between 1987 to around 2005 are currently doing a very good job for us. According to the Farm Carbon Toolkit every hectare of broadleaved deciduous trees will absorb around 4,761Kg of carbon dioxide per year. In addition, for every 1,000m of managed hedgerow, a further 1,175 Kg of CO2 is absorbed every year. On our farm we have doubled the area of woodland over the last thirty years to over 9 hectares and increased the length of hedgerows to over 14,000m, so our woodland and hedgerows are absorbing over 59 tonnes of CO2 every year.

(To learn more about how plants store CO2 in the soil, have a read of our blog post about why we no longer plough our fields.)

To put this into perspective, an average family car such as our ‘Mellow Yellow Mini’ produces around 117g of CO2 for every kilometre driven, therefore our trees and hedges are removing enough CO2 out of the atmosphere every year to offset over half a million kilometres of driving, which is enough to remove over 40 ‘Mellow Yellow Minis’ off UK roads each year (for the average car use of 11,900 km per year).

With all these great benefits that trees bring to our lives and the world around us, we are certainly going to continue planting trees on our farm. Starting this February, working with the Woodland Trust, we are going to plant up a small area next to a pond with 100 trees, that until recently had scrub and dead elms. This time though, rather than doing all the work ourselves, we are going to invite local people to help us. We will provide the young trees and in return for everyone’s hard work, we will lay on some refreshments to create a real good community spirit. If you would like to join us and plant a tree on Bottom Farm on Sunday 16th February, register for your ticket here.

So yes, I am definitely a Tree Hugger and proud to be called one! Any other prospective tree huggers out there, feel free to sign up to come along in February and plant your very own bit of history in the English countryside.

“A nation that destroys its soils destroys itself”

Franklin D Roosevelt.

As a farmer, I have always known that everything I produce is dependent on the soil I grow my crops in and the rain that falls on them. Without these natural resources, we would fail. However, it is not just farmers that soils are important to. They are the cornerstone for the survival of life on earth and, as former American President Roosevelt appreciated, the key to the prosperity of whole nations and civilizations.

Ever since mankind turned from hunter gatherer to farmer, we have had the sad record of destroying our soils, which led to the demise of empires. Whether this being the Ancient Greeks, where ancient monuments are now surrounded by arid bedrock, in what was once fertile farm land. Or the fall of the Roman Empire, which spread out north and south from Italy, in the attempt to bring food in from new agricultural lands. Or more recently the fall of the Soviet Union, as the population got fed up with constantly queuing for essential staple foods, where in reality they were not producing enough food to feed themselves.

In nature crops and animals grow naturally quite well, but they are a bit randomly spread out. As mankind started to domesticate crops and animals for their needs, they started clearing areas of land to produce more food in a given area. The land was cultivated by the plough, originally a small implement pulled by an ox or donkey, today it is much larger and pulled by tractors. But the principle is the same. The plough turns over and breaks up the soil surface to create a seed bed to plant crops in. The advantages are that it provides soils free from weeds, provides good conditions and soil structure for plants to grow in. It also gives a nutritional boost to the plants as bacteria breakdown minerals for the plants to feed off.

Over time the disadvantages of ploughing however outweigh the advantages. The freshly disturbed surface of the earth is very fragile, especially when it rains, with soil erosion being particularly noticeable on slopes. As rain drops hit the soil surface, water drains down-hill into streams, rivers and eventually into seas and oceans. But the water takes the fertile soil particles with them, which in time can remove the soil completely; think of those ancient Greek monuments standing on top of rocky outcrops. But it still happens today as this satellite image of the UK clearly shows. Now whilst I am all for us exporting more products to our friends in Europe, I am not sure we want to be sending them our fertile soil.

This satellite image, taken on 16 February 2014, shows how soil is washed off our fields and out into the sea. ©NEODAAS/University of Dundee

Also, whilst ploughing creates a lovely loose structure for seeds to germinate in, the action of ploughing exposes the soil to oxygen in the atmosphere. This gets all the soil bacteria really excited, similar to a young child being given sugary sweets, running around really quickly, before collapsing in a heap on the floor once the sugar rush is over. The bacteria ‘run around’ in this high oxygen atmosphere, giving lots of nutrition to the crop, but it is short lived as the bacteria eat up the store of carbon in the soil, respiring as they do so, and thus release the stored carbon to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. This has the double negative effect, of gradually reducing the nutritional content of the soil and increasing the global warming effects of increased CO2 in the atmosphere.

Having learnt much on soil quality over the years, I took the decision not to plough on our farm back in 1998. Admittedly, my incentive was not just to save the planet, but also to save money as ploughing is an expensive operation. Although it was known my crop yields could reduce a little, hopefully this would be more than compensated by reduced costs. When I stopped ploughing, I made lots of mistakes as yields reduced dramatically for a short period, as well as weed pressure increasing. Our neighbours thought I was a bit daft – they may be right on that one. But over the years, I have learnt an awful lot as the system has improved. The theory of not ploughing is that naturally plant roots and creatures like worms improve soil structure. The bacteria and other micro fauna improve the soil health and biology, converting old plant residues and mineral content of the soil into plant food. So by not ploughing, the soil structure and organic matter content gradually improves year on year and, the carbon from the soil is not released to the atmosphere as CO2. I continue to learn from my experiences as we are making a healthy environment for the plants to grow in, but this is the underlying theory.

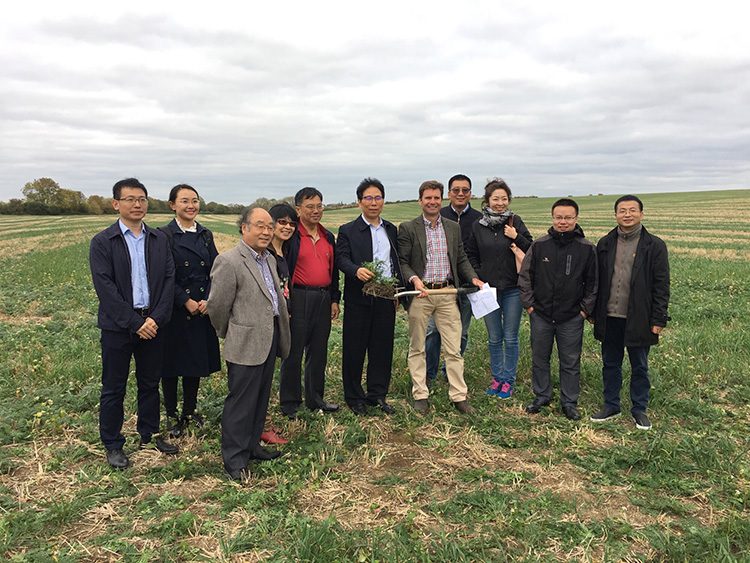

Delegation from China, including Deputy Director General of the Ministry of Agriculture and the Chinese delegate for the United Nations Environment team.

Today, soil health is something that governments around the world are realising is important and we should be doing something to improve our most important natural asset. I was especially proud recently when, along with LEAF, I hosted a delegation from China which included; The Deputy Director General of the Ministry of Agriculture and the Chinese delegate for the United Nations Environment team. They were very interested in what we are achieving with our soil health on the farm.

Plenty of commentators accuse agriculture of being a huge cause of global warming from CO2 emissions, however I can show from what we are doing on our farm, agriculture can play a major role in reducing CO2 emissions when looking after our soils.

Below Black Barn field, Bottom Farm

The graph shows how the soil on our fields is improving in quality, by increasing in soil organic matter. To put this another way, we are actively absorbing CO2 out of the atmosphere and locking it into our soils. If this is repeated around the world, the benefits could be enormous; it has been estimated that agriculture could reduce global CO2 emissions by between 10% to potentially 30%. The graph also shows the increase in Cation Exchange Capacity (C.E.C). In basic terms as the CEC increases, there is more nutrition within the soil for the plants to grow healthily.

So, in the space of a few years of trying to work with nature, the results clearly show we are creating a healthier, more nutritious environment for crops to grow in. Not only is this good for the soil and the wider environment, but it is good for us also, as healthy soils grow healthy crops and healthy crops create healthy food for us to enjoy eating.

Learn more about our environmental credentials here and where to buy our LEAF Marque Cold Pressed Rapeseed Oil here.

After several years of trying, I am excited to report that renewable energy has returned to Bottom Farm!

As a family we have always been environmentally aware and energy efficient even if, originally, we didn’t realise it. Let me explain. Most actions we take as a society to become more energy efficient are driven nowadays by doing the right thing for the environment and for future generations. In my mind this is the right thing to do. However, these actions are also good common sense and a great way to save a bit of money.

Many years ago, my pioneering Grandfather became one of the first people in Britain to generate electricity from a windmill for his home, see the timeline on our website showing this. He also built his own solar panels to heat water, so he could have a hot bath in the evenings. Later, my Father made his own central heating boiler to burn waste timber from the local timber yard to heat our house. I remember as a teenager in school holidays, having to fill and light the boiler every morning with six-foot lengths of off-cut pine, leftover from the manufacture of garden sheds and fences. Without this boiler, we wouldn’t have hot water, or a warm house.

Today such practices would be applauded as great examples of people doing their bit for the environment. However, the reality was that both my Father and Grandfather, were driven by ways to run their homes efficiently in order to save a bit of money. Plus they both enjoyed trying to do things a bit differently. Eventually the timber yard closed down and the boiler was at the end of its life, so it was replaced with a modern oil-fired central heating boiler.

Duncan’s grandfather’s home-built windmill

Move forward a few years and people became more aware of our effect on the environment and potential ways to ‘reduce one’s carbon footprint’ by creating ‘renewable energy’ using a whole range of new and exciting technologies such as: solar photo voltaic systems; biomass boilers or combined heat and power; ground source heat pumps; rain water harvesting and several more. We have collected rain water both on the farm and at our home for many years. Our youngest daughter, Amelia, was talking about this in her geography class only the other day, not realising that this is still relatively unusual, as she assumed this was standard in all homes and couldn’t understand why not.

Apart from rainwater harvesting and other good practises like using LED lighting, or even encouraging people to turn lights off, or to keep doors closed when it is cold, we have not had any renewable energy at Bottom Farm for over fifteen years. This was not for lack of trying though…

Around the turn of the Millennium, we looked at installing a wind farm on the farm. I was keen to follow in my Grandfather’s footsteps and thought people would love the idea, but unfortunately our neighbours in the village were not quite as enthusiastic as I was. We gave up on that idea soon after. Later, when Farrington Oils needed more electricity, I looked at putting solar panels on the factory roof, however it turned out that as we live in a small village, with Bottom Farm being at the end of the power line, we had the wrong sort of electricity and not enough of it to work with solar panels. So again, a dead end.

Our grain store, pre-solar panels

Our grain store, during solar panel installation

Now after three years of planning, working with the local electricity supplier and substantial investment on our part, we now have a new electricity supply to Bottom Farm. The local electricity supplier is delighted with this as they can give a more reliable supply to the rest of Hargrave, meaning that lights and televisions will stay on in the winter months. More importantly, it is now the right sort of electricity to work with solar panels!

We now finally have solar panels on two barn roofs, which will generate over half the total electricity we use at Bottom Farm. So, when you enjoy using Mellow Yellow in your cooking, just think, your little bottle of sunshine is grown using the power of the sun and then cold pressed with the power of the sun too. Surely that’s got to be good for all our futures?

Our grain store with completed solar panels

Duncan Farrington

Here at Farrington’s, we don’t use neonicotinoids on our rapeseed crop. This is for many reasons, mainly because of the concerns related to this pesticide and the effect on bees. You can read more about our bee friendly rapeseed and what else we do to keep the bees on our farm healthy and happy here.

Friends of the Earth, a campaign group looking for solutions to environmental problems, is concerned about the impact of neonicotinoids on bees and other pollinators and urged farmers to join them in pledging not to use neonicotinoids. We were asked us to join the Bee Friendly Shoppers Guide to Rapeseed Oil, of which we are 1 of only 7 rapeseed oil producers on this list. Of course we said yes! The guide aims to educate shoppers on which oils to buy, and how these oils are helping Britain’s bees. As part of the guide, we have pledged not to use the three neonicotinoid pesticides which are currently restricted across the EU, and will continue to avoid these pesticide even if the ban is lifted.

The Bee Friendly Shoppers Guide to Rapeseed Oil is supported by a number of leading chefs. These include Kevin Gratton, chef director for Mark Hix Restaurants, David Everitt-Matthias of Le Champignon Sauvage, Martin Burge, executive chef at Whatley Manor Hotel & Spa and Tom Hunt, eco chef owner of Poco Tapas Bar. Friends of the Earth, alongside the supporting farmers and chefs, are asking consumers to support the initiative by buying the bee-friendly rapeseed oils detailed in the guide.

Friends of the Earth’s Bee Campaigner, Nick Rau, said “We’re delighted Farrington’s Mellow Yellow is standing up for Britain’s bees by pledging not to use these three bee-harming pesticides on their rapeseed crops. They deserve our support. We hope more farmers and producers follow their lead and say no to these neonicotinoid pesticides. Nature-loving shoppers can back this pioneering initiative by checking out the Bee Friendly Shoppers Guide to Rapeseed Oil and choosing these products in supermarkets, local stores and online.”

To read more about the Bee Friendly Shoppers Guide to Rapeseed Oil, please visit: http://www.rapeseedoilguide.com/

Sometimes I just have to spend a few undisturbed days in the office with my head buried in spreadsheets trying to do some strategy planning for the future of the business. As well as being vitally important, I do enjoy trying to work out the best way for all the pieces of the jigsaw to fit together.

Firstly I will be updating my whole farm Environmental Policy. This document is all about what we stand for and looks at everything from water resources and wildlife, to staff and the machinery choices we make on the farm. It is a true record of where we are as a business, as well as putting some targets for the following year. I update this annually, following discussions of what our ambitions are for the year.

Then there are the cash flow forecasts that need completing for this year and next, a vital tool to help give an indication of where and when the money is going to come from and what we will have left to invest. Farming, like any other business, does not have a crystal ball, particularly when it comes to predicting future weather and commodity trends, but it does give me an indication to start planning around.

Business planning is a combination of strategy, mixed with plenty of compromise, a bit of aspiration and a realisation that not everything can be done at once. For example over the last couple of years the farm has had to cut back its shopping list drastically due to a poor harvest two years ago. The tractor we recently bought, I wanted last year, but couldn’t afford. Now I am looking at the investments required for the next two years and trying to prioritise those, whilst trying to keep the business agile.

Our fourteen-year-old combine harvester is a crucial piece of machinery. A wheel recently departed from the rest of the machine on the road and the combine ended up in the ditch. Thankfully no serious damaged was done to people or machine, however, this brings home the fact that we need to look at replacing this over the next couple of years and at around half a million pounds for a new one, I will be looking for another used machine. For this year, one of the things near the top of the list is a solar power system to go on the oil factory roof. This ticks many boxes both financially and environmentally, so as long as I can get the figures to work, it should become a reality over the next few months.

Farming Diary

From LEAF Demonstration Farmer Duncan Farrington

Oils

Oils Rapeseed Oil

Rapeseed Oil Chili Oil

Chili Oil Dressings

Dressings Blackberry Vinaigrette

Blackberry Vinaigrette Classic Vinaigrette

Classic Vinaigrette Balsamic Dressing

Balsamic Dressing Honey & Mustard

Honey & Mustard Ultimate Chilli Dressing

Ultimate Chilli Dressing