Today is World Soil Day: the 11th annual global campaign focused on the importance of healthy soil and to advocate for the sustainable management of soil resources.

The theme of this year’s campaign is caring for soils: measure, monitor, manage, which highlights the importance of research and data in understanding the soil characteristics that underpin decision-making on soil management for food security.

Sustainable soil management is a priority here on our farm. We firmly believe that ‘healthy soil = healthy oil’ and as such we place a huge emphasis on researching, testing and understanding our soil to ensure we are farming the land for long-term, sustainable outcomes.

Working with esteemed organisations like LEAF (Linking Environment and Farming) and One Carbon World we have been able to achieve total carbon neutrality as part of our wider commitment to sustainability. And a huge part of this has been working collaboratively to understand the soil in which we grow our crops.

We are a LEAF Marque accredited farm and a LEAF demonstration farm that sees farmers and industry come together to look at the soil and share best practices so we can constantly evolve our approach. It’s not a one size fits all – there are challenges and a lot of hard work! But through the sharing of key learnings and information, we can constantly tweak our approach and push for more sustainable food production models here in the UK.

Put simply, we think soil is amazing and we want to do everything in our power to help it thrive. We don’t plough to ensure our soil can store as much carbon as possible. We use cover crops to keep the soil covered, adding more organic matter when needed. And we use a wide rotation of crops, alternating between 4 different crops, in addition to cover crops year on year, so if one crop uses up a lot of one nutrient, we can plant a crop that adds that nutrient back into the soil the following year.

By keeping the soil fertile and healthy, we can ensure it stores more carbon to grow nutritious crops in our fields. Because nutritious crops = nutritious food. It’s simply about respecting the land and the process to ensure the best possible outcomes for people and planet.

Our team headed to the Weetabix Northamptonshire Food & Drink Awards last week—an annual event that celebrates local food and drink suppliers, growers, and producers in Northampton. It was wonderful to be in a room with other like-minded folks, all striving for the same thing: to ensure the food we grow and create in the county is not just delicious and high in quality but also sustainable, ethical, and beneficial to everyone along the production line.

The Farming Environment Award is sponsored by Weetabix and recognises protocol growers who have supplied Weetabix within the last two years. It looks at growers who have taken meaningful steps to reduce the environmental impact of wheat growing, whilst taking measurable actions to reduce carbon footprint, promote biodiversity and practice regenerative agriculture.

We are so proud of our farm’s sustainable credentials and our ongoing work to promote biodiversity, so when Farrington’s Farm was announced as the winner of the GOLD award, we were naturally delighted! Of course, it’s always wonderful to win an award, but when it recognises the work, time, effort, and collaborative journey our team has been on to nurture our land and help it thrive, it is even more special.

Here are some of the reasons that led to our award win:-

– We are committed to regenerative agriculture and environmental preservation. And we are always looking at ways in which we can nurture our soil to ensure all of our crops, from wheat to make Britain’s favourite breakfast cereal, to rapeseed which we press on site to make Mellow Yellow cold pressed rapeseed oil is the absolute best it can be.

– We are a LEAF Marque accredited producer and a LEAF demonstration farm. This means we have been independently verified under LEAF’s robust sustainability credentials.

– We stopped ploughing in 1998 and practice minimum and zero tillage to establish crops. Allowing worms and other little soil beasties to create a healthy soil full of life to help us grow our crops.

– To date, around 6,000 trees and over 8km of hedges have been planted, along with extensive wildlife habits created, improved, and maintained around the farm.

– Our farm was certified Carbon Neutral in 2020.

– A network of over 8km of well-maintained public rights of way invites people to enjoy the countryside.

Find out more about our approach to sustainability and our credentials.

As with most foods that you’ll find on the shelf, there are huge discrepancies in flavour, taste and texture, the majority of which come down to two things – quality of produce and production techniques.

Cultivation, ingredients, provenance, handling, packaging, storage – all of these factors play a HUGE role in how food looks, tastes and performs when we cook – not to mention the health benefits that it can bring to the table. Perfecting these processes form the foundation of everything we do here at Farrington’s Mellow Yellow, but it’s in our core method: the act of cold pressing our seeds, where the real conduit to quality and value lies.

A better way of doing things

In the same way that a cold pressed juice retains more vitamins, enzymes, minerals and antioxidants than it’s processed counterparts, cold pressed rapeseed oil offers very similar benefits. We never expose the seeds to heat, and we never add anything artificial. Our method simply allows us to extract every ounce of flavour from our seeds whilst maintaining nutritionally beneficial plant sterols, vitamins and healthy fats.

At Farrington’s Mellow Yellow our process is simple: we take the best quality seeds; mechanically squeeze them to release the oil and then filter through a large tea style strainer, before putting the fresh, pure oil in a bottle ready for you to enjoy. As part of this process, we carry out around 39 quality checks on every bottle of oil or salad dressing we make, ensuring only the very best is good enough. Simple pure Mellow Yellow pleasure!

Most culinary oils consumed globally are refined as opposed to being cold pressed. For olive oil this process includes using hexane solvent, phosphoric acid, caustic soda, water and temperatures reaching 250°C. For rapeseed oil the process includes hexane solvent and temperatures around 90°C. These industrial processes lose much of the quality, flavour and colour characteristics of the original oils. Refined olive oil is also referred to as pomace oil.

As the magic ingredient behind the healthy Mediterranean diet, olive oil is often perceived as the gold standard in oils. And it’s true – olive oil is great! But so are other oils too. And when it comes to health benefits, rapeseed oil supersedes olive oil in many ways, particularly when the oils are cold pressed.

At Farrington’s Mellow Yellow, we’re proud to produce a rapeseed oil with seeds originating from LEAF Marque grower farms and our own family farm here in Hargrave. We value traceability enormously and we are proud to be at the helm of our production line – sowing, growing and pressing the rapeseed oil into high quality, delicious bottles for you to enjoy at home.

Inflation; The cost of living; Global shocks; Food shortages; Extreme weather. The last couple of years have played host to an onslaught of major events, resulting in big price increases to the things we buy – particularly food.

We know the food service industry has been hugely impacted by these events. So, in this post we’re focusing on our Mellow Yellow values: the importance of ingredients, provenance, quality and fair pricing in the face of what appears to be huge changes for the British food industry. As producers of fine quality rapeseed oil, we understand that as chefs, business owners and fellow producers, you don’t want to compromise on values – especially when it comes to ingredients: the bread and butter of your business.

And we’re singing the praises of rapeseed oil – the gold nectar of our business – that brings a wealth of creative opportunities and quality culinary moments to your kitchen, without the same price hikes we’re witnessing across the olive oil industry.

The changing landscape of culinary oils

The Ukrainian conflict combined with the extreme heat and wildfires in the Mediterranean have led to massive inflationary pressures on culinary oils over the last two years, with prices doubling in many cases. Whilst the initial shocks of the Ukrainian conflict have somewhat subsided, the continued difficulties in olive oil producing regions due to extreme weather conditions and disease killing olive trees, is leading to a longer-term shortage of olive oil globally, with big price increases as a result.

These price hikes have inevitably imposed huge pressures on business margins, which is why, here at Farrington’s Mellow Yellow we have worked hard to keep price rises to an absolute minimum. It’s fair to say it’s not always been easy! Our electricity bill tripled at one point and the jerry cans we use seemed to be creeping up in cost with every new order. As a fair wage employer – we’ve also been conscious to ensure that our loyal team have fair pay rises. Despite these challenges, we’ve managed to pick our way through the hurdles and avoid reactionary panic price increases.

Excellent value for money

We like to think that our cold pressed Farrington’s Mellow Yellow Rapeseed Oil, Chilli Oil and range of dressings continue to offer excellent value for money, helping you maintain your margins at a time when other ingredients are escalating in price, with zero compromises on the quality of your food.

Looking at the graph below, it is clear to see how Mellow Yellow rapeseed oil compares to extra virgin olive oil (EVO) and pomace oil over the last two years, showing that you can continue enjoying the wonderful taste, versatility, health and sustainable values of Mellow Yellow, without a negative impact to your bottom line.

EVO has nearly doubled in price, while the inferior refined pomace oil has increased to the same price as Mellow Yellow. With Mellow Yellow cold pressed rapeseed oil, you have the opportunity to use a premium, sustainably produced British oil with similar provenance to EVO, whilst it’s mild subtle nutty flavour and high smoke point make it truly versatile in the kitchen; it is the oil of choice for much of your culinary requirements.

There’s no need to resort to a refined commodity pomace oil when Mellow Yellow tastes better, performs better and is better for your bottom line. A premium quality ingredient that works hard for you in your kitchen. That’s the Mellow Yellow promise. That’s the Mellow Yellow value.

Everyone has a favourite culinary oil in their kitchen, you may use different oils depending on the occasion. Some people worry that some oils may be ‘bad’, and others are ‘good,’ often picked up from different marketing messages, urban myths, or the occasional extreme sensationalist social media campaign.

Like most oils on the shelf, rapeseed oil has had its share of unfair criticism during it’s time. So, in this post – the second in our values campaign – we wanted to address some of the myths and talk more about all of the good stuff rapeseed oil brings to your health and your kitchen.

Balance of healthy fats

Rapeseed oil has an excellent balance of different fats which support our general health and well-being, including heart health and maintaining healthy cholesterol levels, brain, skin and eye tissue development. It also has the lowest saturated fat of any culinary oil at 6%, compared to olive oil 14%, butter 51%, coconut oil 91%. Read more about fats here.

Omega 3 is an essential fatty acid that we get from our diets to regulate cholesterol, aid brain and eye health as well as other bodily metabolic functions. It is found in certain nuts and seeds, including rapeseed, with a content of 10% in cold pressed rapeseed oil, compared to nothing in many oils including palm, sunflower and coconut oils, and only 1% in olive oil.

Not only is cold pressed rapeseed oil the only high temperature culinary oil to contain Omega-3, it also has the perfect balance of Omega-6 which we need in small amounts in our diet. We require around two parts of Omega-6 for every one part of Omega-3 – the exact ratio found in cold pressed rapeseed oil. It’s an important balance to strike for good health, but we often see it go off course – especially in the case of highly processed western diets which can result in people consuming excessive amounts of Omega 6 – leading to negative health outcomes like poor heart health, inflammatory disease and depression.

Enriched with vitamins

An excellent source of vitamins E, K and provitamin A – cold pressed rapeseed oil is a great way to consume small amounts of these daily vitamins for general health.

Vitamin E is a powerful antioxidant that helps maintain healthy skin and eyes, whilst serving as a natural immune booster. Vitamin K regulates blood clotting, whilst provitamin A (also known as

a carotenoid) is an important antioxidant in the prevention of various types of cancers, as well as playing a crucial role in heart and eye health.

Sunflower oil is a very good source of Vitamin E at 73%, with rapeseed and olive oils at 30%, whilst coconut oil only has 1%. Cold pressed rapeseed oil and other brassica crops are good sources of vitamin K. Whilst rapeseed oil has around 5 times the antioxidant properties of Carotenoids (provitamin A) compared to olive oil.

Powered by Plant Sterols

Plant sterols are natural, fat-soluble compounds found in plants that are very efficient at reducing cholesterol levels. They are considered to be the most effective single food that can lower cholesterol as part of a healthy diet and lifestyle.

Rapeseed oil is an excellent source of these healthy compounds, with over double the sterol content of extra virgin cold pressed olive oil. Much of the plant sterol properties are lost in refined oils, but our cold pressing method ensures that Mellow Yellow maintains these cholesterol-reducing properties, making it a preferable choice for health in comparison to refined rapeseed oil. Interestingly, the plant sterols that are lost in the refined rapeseed oil process, are isolated and sold on to food manufacturers, to add back into products allowing them to claim the health benefit: “contains plant sterols.” An unnecessary complication some might argue!

Erucic acid

Erucic acid is a bitter-tasting, mono-unsaturated fatty acid produced in many green plants, constituting 30 to 60% of the total fatty acid content of mustard seed and traditional rapeseed varieties. There has been much speculation on the negative effects of erucic acid on human health, though no confirmed negative health effects have been formally documented in humans.

This combination of bitterness and potential health concerns have led to many varieties of rapeseed oil being naturally bred with lower levels of erucic acid (with a legal maximum level of under 2% for culinary rapeseed oil), resulting in a more subtle, nutty flavour. At Mellow Yellow, the content is in the region of less than 0.02% – a result of the rigorous testing we carry out on the best quality seeds before we press a single drop of oil.

The difference is Mellow Yellow

We believe a healthy, varied and balanced diet trumps the wide array of manufactured nutritional supplements you can buy off the shelf. It’s championing home cooking instead of processed food. And making authentic ingredients that are grown ethically and sustainably for health and not quick financial gain. That’s the Yellow Mellow ethos. That’s the Mellow Yellow value.

We hope you try our Rapeseed oil in your recipes, bring a little heat to the table with our subtle award-winning Chilli Oil and use our delicious salad dressings to add flavour and support the digestion of fat-soluble vitamins in your salads.

Why not browse our recipes and try something new? Not only will you be getting great quality and value for money, but a big win for health too

Global pandemics, inflation, conflicts, food shortages, climate change…. there’s no denying the fact that the world faces multiple challenges right now, many of which are having a big impact on the cost of living and consequently, the cost of food.

Here at Farrington’s Mellow Yellow, we’ve seen first-hand how this has impacted production lines – raising the price tag for everyone along the way, and eventually you – the end consumer. We’ve fought hard to keep the cost of our Mellow Yellow Rapeseed Oil and dressings as low as possible and we wanted to share a little bit about how (and why) we’ve chosen to do that.

Making good quality rapeseed oil accessible

Food brings people together and is a wonderful salve during testing times. A symbol of a life shared, cooking is a part of who we are, and we firmly believe that putting a great meal on the table, made with quality ingredients, shouldn’t cost a small fortune.

There are a few reasons why we’ve seen the prices of culinary oils explode in the last two years. The Ukrainian conflict, combined with the extreme heat and wildfires in the Mediterranean have led to huge inflationary pressures, with prices doubling in many cases. Whilst the initial shocks of the conflict have somewhat subsided, the continued difficulties in olive oil producing regions due to extreme weather conditions and disease destroying olive trees, is leading to a longer-term shortage of olive oil globally, with escalating price increases as a result.

While many oils have increased in price, at Farrington’s Mellow Yellow we have manged to keep price rises to an absolute minimum. This of course, hasn’t come without challenges! The cost of our electricity tripled at one point and the price of our glass bottles increased dramatically due to the high energy used to manufacture glass. It’s been tricky at times, but we have managed to pick our way through the hurdles to avoid the difficult scenario of hefty price increases and wage decreases, ensuring that our loyal team continue to have fair and reasonable pay. And you – our loyal customers – can continue to enjoy Farrington’s Mellow Yellow in all of your favourite dishes.

The graph below illustrates how Mellow Yellow Cold Pressed Rapeseed Oil compares to a leading brand of olive oil over the last two years, showing that you can continue enjoying the wonderful taste, versatility, health and sustainable values of Mellow Yellow, without costing the earth.

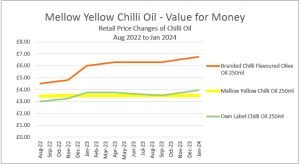

This next graph shows a similar story with our delicious chilli oil which is gaining a loyal following of customers who enjoy something a little warmer in their recipes or simply drizzled over pizza, salad and favourite meals.

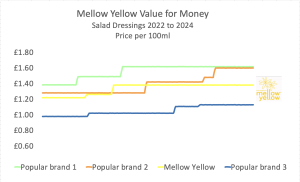

This final graph shows how Farrington’s Mellow Yellow dressings remain excellent value for money in comparison to other leading brands. We have compared prices against similar products, but it is only a Mellow Yellow dressing that is made from unrefined cold pressed rapeseed oil, with great quality ingredients and absolutely ZERO additives, preservatives, or artificial stabilisers.

There are of course cheaper alternative dressings, but many of these come with a long list of processed ingredients. Mellow Yellow dressings are made just as you would do at home, but with our thoughtful ingredient profile and delicious flavours, you can leave the hard work to us and simply enjoy drizzling Farrington’s Mellow Yellow on your favourite salads!

Whatever your choice in oils and salad dressings, if you haven’t already tried the delicious flavours of Farrington’s Mellow Yellow, now is the perfect opportunity to search them out knowing that not everything good costs the earth. And if you’re an existing customer who is enjoying Mellow Yellow products in your home cooking, we would like to give you our heartfelt thanks for supporting our family business. We hope that our great values continue to inspire you!

Here at Farrington’s Mellow Yellow, we are very proud of the delicious range of rapeseed oils and salad dressings produced on our farm. Ever since launching Mellow Yellow in 2005 as the first cold pressed rapeseed oil in Britain to be sown, grown, pressed and bottled on the farm, I have been driven by the ambition to produce the very best we can; to create sustainable food with quality and integrity at its heart. From our small beginnings producing a few bottles a year, to today, with the support of our dedicated team in our factory at Bottom Farm, those values remain as important today as they were on day one.

Over the coming months, we’ll be sharing with you some of the core values behind Mellow Yellow. Because in the current climate, we believe that value is imperative to get right – for you, our valued consumer, but also for everyone involved in the journey from seed to bottle.

It could be the health values of Mellow Yellow, which as a cold pressed rapeseed oil has the lowest saturated fat of any culinary oil; is high in Omega-3; and packed with cholesterol busting plant sterols (over twice as much found in extra virgin olive oil, for example). Then there is value for money. At a time when the price of food is rising alongside the escalating cost of living, Farrington’s Mellow Yellow products offer exceptional value in comparison to many alternatives, some of which have more than doubled in cost.

We’ll look at the environmental and social values of Mellow Yellow, which as an oil grown from British rapeseed to LEAF Marque standards sets the bar for others to follow. The appreciation for our team – the heart and soul of our business – all of whom are signed up to the Living Wage Foundation, ensuring jobs that are valued with fair pay for all. Indeed, we are delighted to be accredited by the Good Business Charter and VERY proud to be a recipient of the Queen’s Award for Enterprise for Sustainable Development.

Lastly, let’s not forget the values of Farrington’s Mellow Yellow in your kitchen; as an excellent roasting oil with its high smoke point, or its subtle nutty flavour – a truly versatile ingredient for so many recipes. And our delicious salad dressings – each made with quality, additive-free ingredients, so you can confidently drizzle onto salads and into marinades, knowing there’s nothing unrecognisable in our quality blends.

People often ask us what they can use their bottle of Mellow Yellow for, so we created a huge bank of recipes to inspire you to get creative in the kitchen. From breakfast and baking to dairy-free, family meals, dips (and everything else in between) there’s plenty of inspiring ways to enjoy Mellow Yellow and try something new.

Value for people and planet is at the heart of everything we do here at Farrington’s Mellow Yellow, and I hope you’ll join us as we share more about the importance of values to us as a business.

Duncan Farrington.

Cultivating Sustainability: The Power of Partnership with LEAF

In an era where climate change and environmental degradation pose significant challenges, the agricultural sector has a pivotal role to play in fostering sustainability. One organisation at the forefront of this movement is LEAF (Linking Environment And Farming). With a passionate commitment to promoting sustainable farming practices, LEAF has been driving positive change for over 30 years.

This blog post delves into LEAF’s mission, their initiatives, and the transformative impact they create by partnering with agricultural stakeholders worldwide.

Our work with LEAF:

As a LEAF Demonstration farm and LEAF Marque producer, we are very proud of the work the LEAF team do to encourage other farmers to take a more sustainable approach to their farms.

In 2021, we were awarded a Queen’s Award for our industry leading approach to sustainability: from our commitment to carbon and plastic neutrality, to our LEAF Marque standards, to Duncan’s work monitoring and increasing the carbon stored in our soils.

Understanding LEAF’s Mission:

LEAF’s core mission revolves around connecting farmers and consumers to promote environmentally responsible and sustainable food production. Established in 1991 in the United Kingdom, LEAF has grown into an international organisation, spreading its ethos of sustainable farming far and wide. Their approach combines practical, science-based solutions with community engagement, fostering a holistic approach to agricultural sustainability.

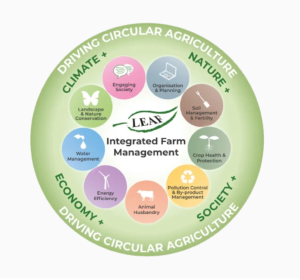

Integrated Farm Management (IFM):

At the heart of LEAF’s philosophy lies Integrated Farm Management (IFM). It encourages farmers to adopt best practices that enhance biodiversity, minimise chemical usage, and improve energy efficiency. IFM is made up of nine sections:

1. Organisation and Planning

2. Soil Management and Fertility

3. Crop Health and Protection

4. Pollution Control and By-product Management

5. Animal Husbandry

6. Energy Efficiency

7. Water Management

8. Landscape and Nature Conservation

9. Engaging Society

By embracing IFM, farmers can optimise their land’s potential while safeguarding the natural resources that sustain us all.

The LEAF Marque:

One of LEAF’s most recognised initiatives is the LEAF Marque, a certification scheme that identifies sustainably produced food to consumers. By displaying the LEAF Marque logo on our Mellow Yellow products, it assures consumers that they come from farms practicing environmentally responsible methods. This strengthens trust between consumers and farmers, driving demand for sustainable products and incentivising farmers to adopt more sustainable practices.

Farm Demonstration Network:

People have always been at the heart of LEAF’s vision of a world that is farming, eating and living sustainably. Building knowledge and understanding of sustainable farming helps highlight the connections between all living things – soil, plants, animals and people.

As a LEAF Demonstration Farm and LEAF Open Farm Sunday host farmer, we welcome people from all walks of life to experience farming first hand. Bringing people closer to farming and how their food is produced, encourages individuals to make sustainable choices in their everyday lives.

LEAF’s dedication to promoting sustainable farming practices has made a substantial impact on the agricultural sector and beyond. By providing farmers with the tools to embrace Integrated Farm Management, offering the LEAF Marque certification to assure consumers and fostering collaborations through their vast network, LEAF has become a driving force for positive change in 27 countries with over 900 LEAF Marque certified businesses worldwide, including over 40% of UK grown fruit and vegetables grown on LEAF Marque farms.

Working alongside LEAF, agricultural stakeholders worldwide are adopting sustainable practices, enhancing biodiversity and conserving vital natural resources. As we collectively address the challenges of climate change, LEAF’s commitment to cultivating sustainability serves as an inspiring model for organisations, farmers, and consumers alike. Together, with organisations like LEAF leading the way, we can build a more sustainable future for generations to come.

Our Journey to Carbon Neutrality

In a world where environmental concerns have reached a critical point, companies embracing sustainability become beacons of hope. At Farrington’s Mellow Yellow, we have taken a remarkable step towards mitigating our environmental impact. With a resolute commitment to sustainability, we have achieved carbon neutrality while collaborating with esteemed organisations like LEAF (Linking Environment And Farming) and One Carbon World. This blog post delves into Farrington’s Mellow Yellow’s remarkable journey towards carbon neutrality and our partnerships that contribute to a greener, more sustainable future.

The Vision for Sustainability

Even before launching Mellow Yellow, sustainability was at the heart of Duncan Farrington’s farming practises. Working to LEAF Integrated Farm Management principles, he used energy efficient machinery, planted trees hedges and wildflower areas to increase biodiversity, and recognised the importance looking after soils in growing the foods we eat. The principles of doing the right things with Mellow Yellow have always been deeply rooted in our commitment to the environment. From the very beginning, we envisioned creating a company that not only provided high-quality oils and dressings, but also operated responsibly, leaving a minimal ecological footprint. With this vision in mind, we set out on a journey to become carbon neutral.

Becoming Carbon Neutral

Achieving carbon neutrality is no small feat, especially for a company operating in the agricultural sector. We adopted a multi-faceted approach to reduce our carbon emissions and offset the remaining unavoidable emissions. Through meticulous planning, innovative technologies, and sustainable practices, we managed to significantly decrease our carbon footprint.

We invested in energy-efficient machinery, optimised transportation routes and implemented renewable energy sources to reduce emissions throughout our supply chain. We also continue to focus on responsible land management and biodiversity conservation on our’s and our grower farms, supplying rapeseed to our factory, through the LEAF Marque accreditation .

Around the edges of our fields we have wildflowers. In these wildflower meadow margins, as they are known, we have a huge variety of different plant species, insects and birds, improving biodiversity and creating wildlife habitats. As well as providing habitats for insects and improving biodiversity, our wildflowers also help us out on the farm. The wildflowers attract pollinators, which are essential for crop pollination, plus the insects in the wildflowers act as a natural pest control on our crops.

On our roofs we have installed solar panels which generate around 50% of the electricity used in the business. This is combined with installing the latest LED lighting and most efficient compressor to run the bottling machinery, both of which reduce the amount of electricity used. We also encourage everyone to do the simple things like turning lights off when we they are not needed.

Collaborations with LEAF, One Carbon World and AgricaptureCO2

Farrington Oils’ journey towards sustainability was further strengthened by our collaborations with LEAF and One Carbon World. LEAF, a renowned organisation, works towards promoting sustainable farming practices that are beneficial for both the environment and the farmers. Through this partnership, we gained valuable insights and guidance on adopting regenerative agricultural practices that boost soil health and sequester carbon.

One Carbon World is a resource partner of the United Nations Climate Neutral Now initiative, is committed to emission reduction strategies and projects that meet the highest standards, reduce carbon emissions, and contribute to sustainable development. One carbon world played a crucial role in Mellow Yellow’s mission to achieve carbon neutrality. Carbon neutral means achieving net zero carbon dioxide emissions by balancing carbon emissions with carbon removal (often through carbon offsets).

To date our carbon neutrality has been achieved with the help of One Carbon World meticulously calculating carbon footprint from our years of data collected, whilst we have been trying to reduce the total emissions we generate. The net emissions are then offset through United Nations approved schemes.

As a sustainable farm-based business there is an opportunity to offset all of our emissions internally through the carbon dioxide absorbed in the soils we manage on our farm through a process called Carbon Sequestration. This is an area of interest that Duncan Farrington has looked at for over twenty years of analysis of his soils, but it is not yet recognised internationally as an accepted measure to reduce potential greenhouse gas emissions. Since becoming certified as Carbon Neutral, Farrington Oils have been invited to be the British case study in a pan European study called AgricaptureCO2 looking into the measurement and verification of soil carbon content and general farm biodiversity. Through this collaborative project it is hoped that sustainable farming can officially become part of the global solution to help reverse climate change.

Why we don’t plough

The plough turns over and breaks up the soil surface to create a seed bed to plant crops in. The advantages are that it provides soils free from weeds, provides good conditions and soil structure for plants to grow in. It also gives a nutritional boost to the plants as bacteria breakdown minerals for the plants to feed off.

However, ploughing can also be detrimental to the environment for several reasons. Firstly, it disrupts the soil structure, leading to erosion and loss of valuable topsoil, which affects soil fertility and water retention. Secondly, ploughing releases carbon dioxide stored in the soil into the atmosphere, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change.

Sustainable farming can help preserve soil health, reduce carbon emissions and promote environmental conservation.

Empowering Consumers

In addition to our internal efforts, we have also made it a priority to educate and empower consumers to make sustainable choices. We transparently share our sustainability journey with our customers, encouraging you to join the movement towards a greener future. By supporting the Mellow Yellow brand, you become part of a collective effort to combat climate change and preserve the planet for future generations.

Our remarkable achievement at Farrington Oils of becoming carbon neutral is a testament to the power of dedication, collaboration, and innovation in the face of environmental challenges. Our partnerships with LEAF, One Carbon World and AgricaptureCO2 have proven that collective action can make a meaningful impact in the fight against climate change.

Let’s continue to work together towards a carbon-neutral and sustainable future.

Every year at the start of August, farmers are encouraged to share their day online as part of 24 Hours in Farming #Farm24. We took part again this year and shared all the goings on from Bottom Farm.

First, we headed out to find Marvin cultivating. This field was growing wheat this year which has now been harvested, we leave the wheat stubble in the field to biodegrade and nourish the soil. We are planning on planting beans in this field in October and beans need to be planted quite deep into the ground. Marvin has to cultivate the soil to loosen the top layer to make it possible for us to plant the beans. This is a big field and the cultivator needs to be driven quite slowly so this will take the majority of the day!

We then headed back to the farm yard, passing the combine harvester which is having a rest until the spring barley is ready to be harvested.

![]()

Here are the wild flowers we have growing around our spring barley. These flowers provide habitats for insects and is great for pollinators.

We even have these beautiful daisies in the wildflower meadow margins, and Duncan explained these are actually chamomile for making into tea!

The last stop on our way back to the farmyard was these trees. Duncan planted them back in 1989 and they are just a few of the 8000 trees he has planted on the farm over the years.

Heading into our rapeseed oil production area, we watched the team pressing and bottling our Mellow Yellow Rapeseed Oil. We cold press our rapeseed on our farm. Our presses run 24/7 to produce Mellow Yellow Rapeseed Oil for kitchens up and down the country! We call it the process of no process. Simply sow, grow, press and bottle!

We harvested our rapeseed a few weeks ago and this what the little seeds look like. They’re bright yellow inside and packed full of delicious and nutritious oil!

After lunch, Duncan headed out to do some mowing. Tidying up the edges of fields already combined and making sure the various public footpaths we have going through the farm are clear and accessible for people on their daily walks!

Before we harvest the wheat, we need to check the moisture content, still a few more days of sunshine needed for this field! Duncan is winnowing here – blowing air through the wheat to remove the chaff!

We then left Marvin finishing off the cultivating and that was our day!

We had a great time sharing our day on the farm and we hope you enjoyed getting an insight into British farming! See you next year!

Oils

Oils Rapeseed Oil

Rapeseed Oil Chili Oil

Chili Oil Dressings

Dressings Blackberry Vinaigrette

Blackberry Vinaigrette Classic Vinaigrette

Classic Vinaigrette Balsamic Dressing

Balsamic Dressing Honey & Mustard

Honey & Mustard Ultimate Chilli Dressing

Ultimate Chilli Dressing