Cultivating Sustainability: The Power of Partnership with LEAF

In an era where climate change and environmental degradation pose significant challenges, the agricultural sector has a pivotal role to play in fostering sustainability. One organisation at the forefront of this movement is LEAF (Linking Environment And Farming). With a passionate commitment to promoting sustainable farming practices, LEAF has been driving positive change for over 30 years.

This blog post delves into LEAF’s mission, their initiatives, and the transformative impact they create by partnering with agricultural stakeholders worldwide.

Our work with LEAF:

As a LEAF Demonstration farm and LEAF Marque producer, we are very proud of the work the LEAF team do to encourage other farmers to take a more sustainable approach to their farms.

In 2021, we were awarded a Queen’s Award for our industry leading approach to sustainability: from our commitment to carbon and plastic neutrality, to our LEAF Marque standards, to Duncan’s work monitoring and increasing the carbon stored in our soils.

Understanding LEAF’s Mission:

LEAF’s core mission revolves around connecting farmers and consumers to promote environmentally responsible and sustainable food production. Established in 1991 in the United Kingdom, LEAF has grown into an international organisation, spreading its ethos of sustainable farming far and wide. Their approach combines practical, science-based solutions with community engagement, fostering a holistic approach to agricultural sustainability.

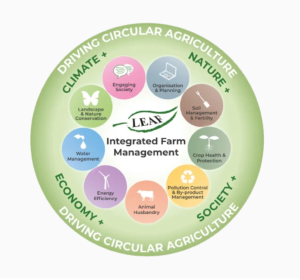

Integrated Farm Management (IFM):

At the heart of LEAF’s philosophy lies Integrated Farm Management (IFM). It encourages farmers to adopt best practices that enhance biodiversity, minimise chemical usage, and improve energy efficiency. IFM is made up of nine sections:

1. Organisation and Planning

2. Soil Management and Fertility

3. Crop Health and Protection

4. Pollution Control and By-product Management

5. Animal Husbandry

6. Energy Efficiency

7. Water Management

8. Landscape and Nature Conservation

9. Engaging Society

By embracing IFM, farmers can optimise their land’s potential while safeguarding the natural resources that sustain us all.

The LEAF Marque:

One of LEAF’s most recognised initiatives is the LEAF Marque, a certification scheme that identifies sustainably produced food to consumers. By displaying the LEAF Marque logo on our Mellow Yellow products, it assures consumers that they come from farms practicing environmentally responsible methods. This strengthens trust between consumers and farmers, driving demand for sustainable products and incentivising farmers to adopt more sustainable practices.

Farm Demonstration Network:

People have always been at the heart of LEAF’s vision of a world that is farming, eating and living sustainably. Building knowledge and understanding of sustainable farming helps highlight the connections between all living things – soil, plants, animals and people.

As a LEAF Demonstration Farm and LEAF Open Farm Sunday host farmer, we welcome people from all walks of life to experience farming first hand. Bringing people closer to farming and how their food is produced, encourages individuals to make sustainable choices in their everyday lives.

LEAF’s dedication to promoting sustainable farming practices has made a substantial impact on the agricultural sector and beyond. By providing farmers with the tools to embrace Integrated Farm Management, offering the LEAF Marque certification to assure consumers and fostering collaborations through their vast network, LEAF has become a driving force for positive change in 27 countries with over 900 LEAF Marque certified businesses worldwide, including over 40% of UK grown fruit and vegetables grown on LEAF Marque farms.

Working alongside LEAF, agricultural stakeholders worldwide are adopting sustainable practices, enhancing biodiversity and conserving vital natural resources. As we collectively address the challenges of climate change, LEAF’s commitment to cultivating sustainability serves as an inspiring model for organisations, farmers, and consumers alike. Together, with organisations like LEAF leading the way, we can build a more sustainable future for generations to come.

Our Journey to Carbon Neutrality

In a world where environmental concerns have reached a critical point, companies embracing sustainability become beacons of hope. At Farrington’s Mellow Yellow, we have taken a remarkable step towards mitigating our environmental impact. With a resolute commitment to sustainability, we have achieved carbon neutrality while collaborating with esteemed organisations like LEAF (Linking Environment And Farming) and One Carbon World. This blog post delves into Farrington’s Mellow Yellow’s remarkable journey towards carbon neutrality and our partnerships that contribute to a greener, more sustainable future.

The Vision for Sustainability

Even before launching Mellow Yellow, sustainability was at the heart of Duncan Farrington’s farming practises. Working to LEAF Integrated Farm Management principles, he used energy efficient machinery, planted trees hedges and wildflower areas to increase biodiversity, and recognised the importance looking after soils in growing the foods we eat. The principles of doing the right things with Mellow Yellow have always been deeply rooted in our commitment to the environment. From the very beginning, we envisioned creating a company that not only provided high-quality oils and dressings, but also operated responsibly, leaving a minimal ecological footprint. With this vision in mind, we set out on a journey to become carbon neutral.

Becoming Carbon Neutral

Achieving carbon neutrality is no small feat, especially for a company operating in the agricultural sector. We adopted a multi-faceted approach to reduce our carbon emissions and offset the remaining unavoidable emissions. Through meticulous planning, innovative technologies, and sustainable practices, we managed to significantly decrease our carbon footprint.

We invested in energy-efficient machinery, optimised transportation routes and implemented renewable energy sources to reduce emissions throughout our supply chain. We also continue to focus on responsible land management and biodiversity conservation on our’s and our grower farms, supplying rapeseed to our factory, through the LEAF Marque accreditation .

Around the edges of our fields we have wildflowers. In these wildflower meadow margins, as they are known, we have a huge variety of different plant species, insects and birds, improving biodiversity and creating wildlife habitats. As well as providing habitats for insects and improving biodiversity, our wildflowers also help us out on the farm. The wildflowers attract pollinators, which are essential for crop pollination, plus the insects in the wildflowers act as a natural pest control on our crops.

On our roofs we have installed solar panels which generate around 50% of the electricity used in the business. This is combined with installing the latest LED lighting and most efficient compressor to run the bottling machinery, both of which reduce the amount of electricity used. We also encourage everyone to do the simple things like turning lights off when we they are not needed.

Collaborations with LEAF, One Carbon World and AgricaptureCO2

Farrington Oils’ journey towards sustainability was further strengthened by our collaborations with LEAF and One Carbon World. LEAF, a renowned organisation, works towards promoting sustainable farming practices that are beneficial for both the environment and the farmers. Through this partnership, we gained valuable insights and guidance on adopting regenerative agricultural practices that boost soil health and sequester carbon.

One Carbon World is a resource partner of the United Nations Climate Neutral Now initiative, is committed to emission reduction strategies and projects that meet the highest standards, reduce carbon emissions, and contribute to sustainable development. One carbon world played a crucial role in Mellow Yellow’s mission to achieve carbon neutrality. Carbon neutral means achieving net zero carbon dioxide emissions by balancing carbon emissions with carbon removal (often through carbon offsets).

To date our carbon neutrality has been achieved with the help of One Carbon World meticulously calculating carbon footprint from our years of data collected, whilst we have been trying to reduce the total emissions we generate. The net emissions are then offset through United Nations approved schemes.

As a sustainable farm-based business there is an opportunity to offset all of our emissions internally through the carbon dioxide absorbed in the soils we manage on our farm through a process called Carbon Sequestration. This is an area of interest that Duncan Farrington has looked at for over twenty years of analysis of his soils, but it is not yet recognised internationally as an accepted measure to reduce potential greenhouse gas emissions. Since becoming certified as Carbon Neutral, Farrington Oils have been invited to be the British case study in a pan European study called AgricaptureCO2 looking into the measurement and verification of soil carbon content and general farm biodiversity. Through this collaborative project it is hoped that sustainable farming can officially become part of the global solution to help reverse climate change.

Why we don’t plough

The plough turns over and breaks up the soil surface to create a seed bed to plant crops in. The advantages are that it provides soils free from weeds, provides good conditions and soil structure for plants to grow in. It also gives a nutritional boost to the plants as bacteria breakdown minerals for the plants to feed off.

However, ploughing can also be detrimental to the environment for several reasons. Firstly, it disrupts the soil structure, leading to erosion and loss of valuable topsoil, which affects soil fertility and water retention. Secondly, ploughing releases carbon dioxide stored in the soil into the atmosphere, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change.

Sustainable farming can help preserve soil health, reduce carbon emissions and promote environmental conservation.

Empowering Consumers

In addition to our internal efforts, we have also made it a priority to educate and empower consumers to make sustainable choices. We transparently share our sustainability journey with our customers, encouraging you to join the movement towards a greener future. By supporting the Mellow Yellow brand, you become part of a collective effort to combat climate change and preserve the planet for future generations.

Our remarkable achievement at Farrington Oils of becoming carbon neutral is a testament to the power of dedication, collaboration, and innovation in the face of environmental challenges. Our partnerships with LEAF, One Carbon World and AgricaptureCO2 have proven that collective action can make a meaningful impact in the fight against climate change.

Let’s continue to work together towards a carbon-neutral and sustainable future.

The environment has always been at the heart of everything we do.

rePurpose Global is committed to tackling the plastic pollution crisis head-on by offering sustainable, eco-friendly alternatives and actively working towards a plastic-neutral future. Together, we are committed to making a tangible difference in protecting our planet and creating a more sustainable future. In this blog post, we will explore the collaboration between Farrington Oils and Repurpose Global, whilst highlighting the shared values and the transformative impact we have achieved in 2022.

Plastic Waste

Global plastic waste production has reached over 400 million tonnes annually. Just 9% of this will be recycled. Most of it will find its way into landfills or leak into nature, creating havoc across coastlines and fragile ecosystems.

Overall, rePurpose Global, has been able to recover a huge 8,845 tonnes of plastic from nature across 6 countries as of December 2022 – That’s about the weight of 491 Million plastic bottles! Of the 8,845 tonnes of plastic, a massive 862 tonnes of plastic was recovered at Project Neela Sagar alone.

Project Neela Sagar

Through Project Neela Sagar, rePurpose Global endeavours to recover over 9,000 tonnes of low-value plastic waste by 2030, while positively impacting the lives of 1,000+ informal waste collectors.

Farrington Oils and rePurpose Global understand the significance of industry leadership in driving sustainable change. By working together, we aim to inspire other businesses within the farming sector to adopt eco-friendly practices. We are deeply committed to sustainability, and our mission is to gradually reduce our plastic footprint year on year.

Becoming Plastic Neutral

You can read how we firstly became Plastic Neutral and the work we have been doing with rePurpose in a previous blog post – simply click here.

If you would like to work out your own plastic footprint, rePurpose have a simple calculator for you here and even have options for individuals to offset their personal footprints and become plastic neutral.

Sources: rePurpose, Neela Sagar 2022 report.

Around the edges of our fields, there’s something really special; wildflowers. In these wildflower meadow margins, as they are known, we have a huge variety of different plant species, insects and birds, improving biodiversity and creating wildlife habitats. In the summer months, these wildflower meadow margins come alive with the buzzing and fluttering of bees, butterflies and many other insects.

As well as providing habitats for insects and improving biodiversity, our wildflowers also help us out on the farm. The wildflowers attract pollinators, which are essential for crop pollination, plus the insects in the wildflowers act as a natural pest control on our crops.

Did you know that you can bring wildflowers into your own garden too? Set aside an area of lawn, part of a border, or if you are limited on space, a large container will do! Either stop mowing a patch of your lawn to encourage long grass to grow for insects to thrive in, provide shelter for small mammals and create feeding opportunities for birds. Or if you’d rather start from scratch, pick a spot of bare, unproductive soil and sow a wildflower seed mix in autumn, or spring if you have a heavy clay soil, rake the seeds, water thoroughly and wait for a beautiful patch of wildflowers to appear come summer.

Here we have just some of the wildflowers growing in our wildflower meadow margins:

Oxeye Daisies

These are native daisies but are bigger and taller than the standard daisies you may see in your lawn. The yellow coloured centre of the oxeye daisy is packed full of pollen and nectar and attracts various pollinating insects such as butterflies, bees and hoverflies.

The heads of these plants can also be used to make chamomile tea.

Buttercups

The pretty yellow flowers are buttercups, they are very common in Britain thanks to our moist soils. They flower from May to August and attract flies, beetles and bees including honeybees.

Clover

We have two types of clover growing: white clover and red clover. These are both very common in the UK and are typically found in meadows, lawns and roadsides. These clovers attract all kinds of bumblebees, and the white clover is particularly loved by the Common Blue butterfly. This lucky wildflower sometimes produces four-leaf clovers, so keep an eye out for one of these!

Common Knapweed

This purple flower looks very much like a thistle and is very common in our wildflower meadow margins. A favourite with butterflies, these flowers are often surrounded by Cabbage Whites and Meadow Browns!

Tufted Vetch

These pretty violet flowers are a member of the pea family and flower from June to September. Also known as ‘cow vetch’ or ‘bird vetch’, it can be found in woodlands, grassland, and even coastal areas. When the seed pods are ripe, they turn black and have a similar shape to peapods.

Sorrel

Commonly found in grasslands, woodland edges and roadside verges, as well as wildflower meadows, this delicate flower adds a sprinkling of bright crimson and pink throughout the green grasses. The arrow shaped leaves have a particularly tart taste, giving this plant its nickname of ‘sour ducks’.

Cow Parsley

With umbrella-like clusters of white, frothy flowers, cow parsley grows very quickly in the summer before dying back. With large, flat umbrellas of small, white flowers and large, fern-like leaves, cow parsley stands out in a wildflower meadow. If you crush the leaves between your fingers, it will give out a very strong, aniseed scent.

Wild Carrot

Similar to cow parsley, wild carrot has umbrella-shaped flower heads, which start out red and bloom into white flowers from June to September. The leaves and roots of wild carrot smell just like the carrots we cook in our kitchens, but the roots do not form the big, orange vegetable we are familiar with. This plant particularly like chalky soils.

We are absolutely delighted to announce that we have won a prestigious Queen’s Award for Enterprise for Sustainable Development! Farrington’s Mellow Yellow is one of 205 organisations nationally to be granted an esteemed Queen’s Award for Enterprise in 2021 and one of only 17 to be recognised for our excellence in sustainable development.

We have been awarded a Queen’s Award for our industry leading approach to sustainability: from our commitment to carbon and plastic neutrality, to our LEAF (Linking Environment And Farming) Marque standards, to Duncan’s work monitoring and increasing the carbon stored in our soils.

“Winning a Queen’s Award for Enterprise is a huge honour, and being awarded it for sustainable development in particular is a real testament to our commitment to the environment! Sustainability is at the heart of everything we do and I am so proud to be recognised for our decades of hard work and dedication in this area.

Now more than ever, we all need to put our planet first, working towards a more sustainable future. I hope that seeing a small company from a village in Northamptonshire win such a prestigious award will encourage other small and medium sized businesses to take the next step in their sustainability journey, so we can all do our bit for the planet.”

– Duncan Farrington

Now in its 55th year, the Queen’s Awards for Enterprise are the most prestigious business awards in the country. Following on from our award win, we will be continuing our sustainability work with Duncan involved in an EU funded project called AgricaptureCO2 working towards creating a globally recognised standard for measuring soil carbon content.

Learn more about how we look after the environment…

Carbon Neutral

We have measured, reduced and offset all of our carbon emissions and achieved the Carbon Neutral Gold Standard from the United Nations. We are also signatories of the United Nations Climate Neutral Now Initiative.

After reducing our carbon emissions through LEAF farming strategies, we offset our remaining carbon emissions by supporting reforestation initiatives and green energy schemes. This means that Farrington’s Mellow Yellow is not adding any emissions to our atmosphere.

Plastic Neutral

We have partnered with rePurpose Global, and we now fund the removal of the same amount of plastic from the environment as we use in all of our packaging.

This means that for every 1 kg of plastic in Farrington’s Mellow Yellow packaging, we fund the removal & recycling of 1 kg of plastic that would otherwise have been landfilled, flushed into our oceans or littered our environment.

LEAF Marque

We are a LEAF (Linking Environment And Farming) Marque producer, this means we are at the forefront of environmentally aware agriculture.

LEAF encourages sustainable and environmentally responsible farming through a system called Integrated Farm Management. In simple terms, this means they encourage farmers to look at each part of their farm individually and ensure the whole farming process is environmentally sustainable.

Soil Carbon Sequestration

Soil is a brilliantly effective carbon store. The world’s soils actually hold more than three times the amount of carbon than is in the atmosphere!

The process of soil storing carbon is called carbon sequestration and through our sustainable farming, we are storing a huge amount of carbon in our soils, stopping it being released into our atmosphere.

Solar Panels

We have installed solar panels on our barn roofs so that the power of the sun not only helps grow our crops, but now also helps power our oil presses.

Our solar panels can be found on two barn roofs, which are generating over half the total electricity we use at Bottom Farm in a completely renewable and environmentally friendly way!

Tree Planting

Trees are fantastic for absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, providing shelter and homes for birds, insects and small mammals, and helping to reduce flooding and soil erosion.

Over the years, Duncan & his father have planted thousands of trees on our farm and last year we held a community tree planting event, getting a further 100 trees in the ground! Read more here.

A couple of weeks ago, Duncan Farrington was honoured to be included in the panel for the annual LEAF Conference. This is a showcase event normally held in the heart of the financial centre of London, bringing together LEAF members with their customers, journalists, international scientists and policy makers, to hear from speakers on the latest global sustainable issues of the day. This year was different as the conference had to take place online, yet it still was incredibly inspiring and allowed the panellists to share their sustainability goals for the future.

The conference was chaired by Tom Heap, BBC broadcaster with many years’ experience in agricultural journalism, and Duncan was joined by Minette Batters, chair of the National Farmers Union (NFU), Jonathan Wadsworth, lead climate change specialist at The World Bank and Chris Buss, deputy director of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Global Forest and Climate Change Programme.

Each of the panellists shared their sustainability stories, goals and wishes for the future. Here is what each one said, which you can watch via video if you prefer.

Duncan Farrington:

I am very proud that Farrington’s Mellow Yellow is the first food brand in the world to be certified as both carbon and plastic neutral. Having been a LEAF Marque farmer for many years, we are used to collecting data on such things as energy use, which is very helpful as a management tool, but I felt we could use this information as the basis of something bigger and importantly commercially rewarding which led to us becoming carbon neutral.

Through small changes, we have made big differences to our carbon emissions. By reducing the intensity of cultivation on the farm, our fuel usage has reduced 60% to 75%, a broader crop rotation has reduced nitrogen fertiliser usage by 13% and solar panels on our barn roofs generate 50% of our electricity. But the biggest gain has been in soil health from the sustainable techniques I have been practising for the last 22 plus years. I have shown through ongoing soil analysis how a particular field’s general soil health has improved, including soil organic matter which has increased by 75%. The net result has been the absorption of an estimated 300 tons of CO2 by one field alone every year. To put this into context, the total net CO2 removal on our farm is enough to off-set the emissions from around 2,400 Mellow Yellow Minis from UK roads each year. So sustainable agricultural soil management has a huge potential positive influence on climate change.

LEAF already do fantastic work as the trusted go-to organisation supporting sustainable food production and there is now an increasing commercial appetite for climate friendly food that LEAF can lead as a consumer facing organisation. This will drive the commercial success of LEAF farmers and growers, which in turn will deliver the step change in innovation and ambition required. Imagine the kudos and effect if LEAF was successful in winning an award from the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge’s Earthshot prize for championing a carbon friendly food system. That would drive real ambition!

My one climate change wish in the near future is to get an internationally accepted certification for soil organic matter. I am involved in an EU consortium hoping to look at how soils can be accurately evaluated on mass scale using satellite data for their soil carbon content. The ambition is to create a trusted certification, to help land managers explore how their actions can affect soil health, creating the financial and moral incentive to manage land in ways to drive the huge potential of carbon sequestration.

Minette Batters:

The game changer for government and political thinking around climate change is COP26. Farming has seen huge impact from ever more severe weather and farmers are already experiencing the impact of climate change. The NFU has set an ambitious target of net zero by 2040 because we really believe farmers can achieve this with the right incentives. We need to focus on more efficient and sustainable farming, and nobody has shown more leadership in this area than LEAF.

We also need to focus on more carbon storage. There is research into beetle banks that is interesting for example. There is a huge amount that can be done by farmers in carbon storage and this is key. Renewable energy is another big area of opportunity. It is incredibly important for a farm’s diversification to look into renewable energy.

There are a lot of challenges around diet. We need to engage with whole foods and nutrition, cooking from scratch and realising that health is dependent on our diet. We need to look at what we aren’t consuming that we can export too. We also need to revolutionise how we think about water. We need to move water around the country rather than letting diffuse water run into the sea. This needs a strong and ambitious working relationship with government.

My one climate change wish is that COP26 is a game changer, that agriculture rises to the fore across the world and we work together to ensure we are deemed an important part of the solution. Climate change is the challenge of our time and I passionately believe our farmers are the solution.

Jonathan Wadsworth:

The World Bank is an international development organisation with a role to reduce poverty and inequality by lending money to governments of poor countries to improve their economy and standard of living. Over the next 5 years, it will invest $200 billion in climate adaption and mitigation projects.

Progress has been uneven across regions and countries. Millions of people are being left behind, climate change exacerbates these inequalities. The poorest and most vulnerable are hardest hit. To have any hope of achieving sustainable development goals by 2030 we must adapt quickly to climate change and reduce emissions, with urgency. The greatest climate challenge at the moment is how to take action now.

The world food system does an amazing job. For the past 50 years, food production has outpaced population growth, adding $8 trillion a year to global GDP. If the food system was a country, it would have the third largest GDP in the world, behind China and the USA. But this performance comes at a high cost to people and the planet.

Our food system is both a victim and a culprit of climate change, but with the right incentives, approaches and innovations, we know it can be a big part of the solution. The good news is that more and more people are becoming more aware and starting to take action.

LEAF is an excellent example of farmers and researchers working together to find and promote climate-smart solutions. This approach merits being massively scaled up to become a real movement of change and the UK could play a major role.

Agriculture is the only sector able to capture carbon from the atmosphere and store it naturally in vast amounts. We must exploit that advantage fully.

The global food and agriculture system needs to deliver three main things:

– To reduce emissions that contribute at least 30% of the mitigation needed set out by the Paris Agreement.

– Widespread adoption of the planetary human health diet.

– More inclusive development

LEAF can play a key role in continuing to demonstrate what can be achieved and influence governments and investors to find the financial and the political will to support and facilitate a great agriculture and food system transformation.

If I had one climate change wish it would be that COP26 is a success and world governments would recognise that food and agriculture is indispensable for addressing the climate emergency.

Chris Buss:

I work around nature-based solutions and land use and protection of nature, restoration of nature and land production systems. Trees are key for farming systems; they bring nutrients into farming systems, regulate water, provide building materials and firewood. It is a win-win system so makes sense to bring trees into farming.

A great example of the role of nature is pollination. The loss of pollinators is estimated to have a net value of $150 billion to $160 billion. There is a loss to consumers by increased prices, but also a loss of profit to farmers too as they have to replace natural systems.

Success for nature would be farmers helping to make and shape policy. As they manage the land, they are closest to nature and are the key partners globally to help integrate nature into our agricultural systems and shape policies to make sure nature is included in their farming strategies.

One successful strategy that we are building with farmers globally, is working to restore land on-farm and off-farm, bringing trees back into the farming systems. This is critical as it provides farmers with more resilient land use systems, secures supply, sequesters carbon and is socially just.

Moving forward, technical support can be provided to farmers, support can be provided to decision makers going into climate change negotiations and we can build land restoration strategies.

LEAF’s 10 Year Strategy

After a lively Q&A session with Tom Heap, LEAF Chairman Philip Wynn and LEAF Chief Executive Caroline Drummond shared the new LEAF 10 Year Strategy. This is a continuation of their work in developing and promoting more sustainable agriculture through Integrated Farm Management. They are going to support the delivery of positive action for climate, nature, economy and society based on their core work and the principles of circular agriculture.

Their vision:

A global farming and food system that delivers climate positive action, builds resilience and supports the health, diversity and enrichment of food, farms, the environment and society.

The mission:

To inspire and enable more circular approaches to farming and food systems through integrated, regenerative and vibrant nature-based solutions, that deliver productivity and prosperity among farmers, enriches the environment and positively engages young people and wider society.

Their 2031 ambition:

LEAF’s ambition is to play a demonstrable part in transforming farming and food systems. Building on their work since LEAF was established in 1991, this will be through the agro-ecological and regenerative benefits of the whole farm, site specific focus of Integrated Farm Management to drive positive action for climate, nature, economy and society. Embracing circular agriculture with health, diversity and enrichment at the centre of all they do. Through the use of management tools, the harmonisation of metrics, technology, innovations, data and Artificial Intelligence, training, research, demonstration, market opportunity, education and engagement, they will support and contribute to the practical delivery of national and global commitment. This will include the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Paris Agreement and the Post-2020 Biodiversity Framework.

You can read the full plan here or watch this short video:

The environment has always been at the heart of everything we do and we are so proud to be officially certified by the United Nations as carbon neutral, highlighting our commitment to sustainability.

What is carbon neutral?

Carbon neutral means achieving net zero carbon dioxide emissions by balancing carbon emissions with carbon removal (often through carbon offsets).

Many large companies and even governments have set carbon neutral goals, typically to achieve carbon neutrality within 10, 20 or even 30 years. Amazon have pledged to be carbon neutral by 2040, the UK government has said they aim to reach this milestone by 2050 and Delta, an American company, have pledged to become the first carbon neutral airline in the next 10 years.

All of these companies have given themselves plenty of time, which can be needed for big corporations. However, we knew that something needed to be done sooner than this. Thanks to our LEAF Marque audits, we have been monitoring our emissions for many years so were in a great position to become carbon neutral a lot sooner. Read on to find out how we became carbon neutral…

How did we become carbon neutral?

The first step was measure. This involved us looking at every part of our business, from each employee’s commute to work, to the amount of electricity used in our office and factory, to the fertiliser used on our fields. We calculated the greenhouse gas emissions from each and this gave us our carbon footprint.

We then signed up to the United Nations Climate Neutral Now Initiative Pledge. This pledge showed our commitment to measure, reduce and offset our carbon emissions. This pledge has been signed by many other companies and governments that are prioritising our environment and making a meaningful difference.

After measure, the next step was reduce. We are constantly working to reduce our emissions and through our LEAF farming practises, we are able to accurately measure this and continue to reduce them. Some of the ways we have reduced our emissions are:

– The installation of solar panels on our barn roofs in 2018 which now produce 50% of our total yearly electricity. In the summer months, we are producing a huge 80% of our electricity from the solar panels!

– We have dramatically reduced our fuel usage on the farm by stopping ploughing in 1998 and since then, have continued to reduce this further by using less fertiliser on our fields as the soil health increases and provides more nutrients to the crops. As well as reducing fuel usage, by stopping ploughing, we are actually locking in huge amounts of carbon dioxide into the soil, you can read more about this here.

– We use GPS systems on all our tractors to make them as efficient as possible, lowering our fuel usage and keeping emissions to a minimum.

– We use LED energy saving bulbs and timers on our lights to keep our electricity usage as low as possible too.

As we are a LEAF farm, we have a yearly audit to ensure we are doing the best to farm in harmony with nature, and we are always working to find new ways to reduce our emissions and our impact on nature!

The next step in our carbon neutral journey was to offset our remaining emissions. We used United Nations approved offsets and have been able to support a reforestation initiative in Uruguay and a United Nations clean energy project.

With this last step completed, we became certified as carbon neutral in January 2020 and received the Carbon Neutral Gold Standard from the United Nations!

What’s next?

Becoming carbon neutral is a fantastic achievement, but we aren’t going to stop there. We aim to be carbon negative, that means we will be absorbing more carbon from the atmosphere than we put into it, so we would be removing carbon rather than adding it.

In order to become officially certified as carbon neutral, we had to use the United Nation’s way of calculating net carbon emissions. this unfortunately meant we could not take into account all the incredible work we do with our soils as the carbon stored in soils is not yet officially recognised as a carbon store. From our own calculations, if this was taken into account, we would already be carbon negative!

Duncan is now involved in European project to find an internationally accepted, verifiable and certifiable method of measuring soil organic content on a continental scale, encouraging farmers and land managers to adopt carbon capturing methods improve their soil carbon content. The project aims to empower farmers to become agents of climate mitigation, where soil carbon and health will become a financial asset for the farmer and provide natural capital for the wider society by reducing global carbon emissions.

This month is #PlasticFreeJuly and we thought it was the perfect opportunity to share our plastic neutral story…

The environment has always been at the heart of everything we do and earlier this year we took the next step in our sustainability journey and became plastic neutral! Don’t worry if you don’t know exactly what this means, read on and we’ll explain.

Becoming plastic neutral is a lot like becoming carbon neutral which is more commonly understood (and something we have also achieved, read more here) but the general idea is that we now fund the removal of the same amount of plastic from the environment as we use in our packaging, meaning Farrington’s Mellow Yellow is certified as plastic neutral.

MEASURE

The first step in becoming plastic neutral was to measure our plastic footprint. We looked at our products and how they are sent out and started listing all the plastic used at each stage. As our bottles are glass with a metal cap, there isn’t a huge amount of plastic on the product itself, but, for example, the label is plastic, as is the little pourer inside our cap. We also had to look at the way we send out our products. When sending large quantities of our glass bottles to supermarkets, we have to wrap each pallet in plastic wrap to stop breakages which would lead to food waste, so this plastic had to be counted.

Once we had a list of all the plastic used, we worked out how much each item weighed and how much of it we use in a year, and this created our yearly plastic footprint. With this figure, we had a really accurate representation of the amount of plastic that we, as a company, are putting into the environment each year. This is our plastic footprint.

OFFSET

Once we had our plastic footprint, we got in touch with rePurpose Global. rePurpose Global are a global community of conscious consumers and business that are committed to taking action against climate change.

rePurpose partnered us with a recycling project in India so that we could directly fund the removal of the equivalent weight of plastic as our plastic footprint.

rePurpose work with vetted recycling projects tackling the waste crisis in India. A lot of the plastic they are removing from the environment is typically low-value plastic, which recyclers don’t often want to collect as it doesn’t bring them as much money. However, this plastic (such as crisps and chocolate wrappers) is incredibly polluting, especially when it reaches our oceans. rePurpose enables the ethical collection and recycling of this plastic, paying the waste workers a fair wage and giving them proper employment opportunities.

We are tackling a global issue, a lot of the UK’s waste is unfortunately exported to developing countries where it is sent to landfill or ends up in our oceans, so working with rePurpose is helping to finance crucial recycling infrastructure and improving wages and working conditions of waste pickers in India.

REDUCE

The next step is to gradually reduce our plastic footprint year on year. We are deeply committed to sustainability, so are searching for the most environmentally friendly options for our packaging. We know that sometimes removing plastic and replacing it with other materials isn’t always ultimately the best option for the planet. For example, plastic bags have the lowest carbon footprint of shopping bags, as long as they are reused many times, whereas a paper bag requires more energy to produce and isn’t as reusable. So when we look at reducing our plastic footprint, it is incredibly important to us that all environmental aspects are considered and the best option is chosen. We are working hard to find the best solutions, so make sure to keep reading our blog posts for more updates!

If you would like to work out your own plastic footprint, rePurpose have a simple calculator for you here and even have options for individuals to offset their personal footprints and become plastic neutral.

Soil health is a big part of sustainable farming and I have been measuring this on one of my fields since 2002. Among the great soil nutrition and health improvements seen in this field due to my sustainable farming practices, I have farmed in a way that has increased soil organic matter (SOM) which has a direct impact on reducing atmospheric CO2 levels. Between 2002 and 2020 I have seen my SOM increase from 3.8% to 6.7% which is a significant amount when talking about soil!

What is Soil Organic Matter?

Soil organic matter is the organic part of soils consisting of plant and animal detritus at various stages of decomposition. Think of dead leaves off trees, straw left behind after crops have been harvested, decaying soil microbes and insects, or old plant roots in the soil.

The organic matter is made up of cells and molecules containing lots of carbon and it can be lost from soils over the years through natural processes, which is sped up if soils are moved intensively, mixing with oxygen in the atmosphere and released as carbon dioxide (CO2). Commonly this occurs when a field is ploughed.

We no longer plough our fields and have worked hard on our sustainable farming methods to keep the carbon in the soil. In the right conditions SOM can be increased over the years, as plants grow, taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere to create plant material through the natural process of photosynthesis. The process of taking CO2 out of the atmosphere and storing in the soil is called carbon sequestration and the soil becomes a carbon sink as it reduces the levels of CO2 in the atmosphere.

Soils have the ability to be fantastic carbon sinks when looked after. In fact, coal and mineral oils that are mined from the ground (fossil fuels) are carbon that has been stored from hundreds of millions of years ago, formed from decayed plants and animals that once grew and roamed the earth.

How does this relate to our farm?

On my field called ‘Below the Black Barn’ the increase in soil organic matter has removed CO2 from the atmosphere, locking it in the ground which is great for reducing global warming as well as making the soil more nutritious for the plants to grow in. The figures are very impressive. We know that for every 0.1% increase in SOM, around 8.9 tonnes of CO2 are sequestered on every hectare of land.

But what does this actually mean?

If my field has increased the total SOM by 2.9% over 18 years, it has absorbed around 258 tonnes of CO2 per hectare (ha), or 14.34 tonnes per ha per year on average. One hectare is around the same size as one and a quarter football pitches.

To put this into context, driving a 1.5lt petrol Mini (our Mellow Yellow Mini) car produces 117g of CO2 per Km. So, for every hectare of our field we are absorbing enough CO2 to off-set nearly 122,554km of motoring, which is equivalent to over 10 years driving for the average motorist!

Let’s look at the whole farm…

This is just off one hectare, but Below the Black Barn Field has a cropped area of around 20ha and our whole farm cropped area is around 272ha. Therefore, from the way we farm our soils, we are sequestering an impressive 3900 tonnes of CO2 per year, off-setting enough CO2 to fly one person 500 times around the world in economy class! (or take 2,778 cars off the road) each year.

The story does not end with the cropped area

We have a medium sized family farm, which not only includes the cropped area, but all the other bits we do around the edges of our fields as part of our LEAF farming and sustainable farming practises. These include areas of woodland and hedges, a grass meadow, areas of native wild-flowers and grass margins. Over the years we have planted well over 8,000 metres of new hedges and over 8,000 native trees on the farm to add to the existing trees and hedges. All these conservation areas can be calculated to sequester a further 240 tonnes of CO2 per year, as well as being areas for wildlife to thrive and prosper.

In summary on our medium sized family farm in Northamptonshire, following our LEAF and sustainable farming principles of a common-sense approach to sustainable agriculture and soil management, we are absorbing over 4,100 tonnes of CO2 per year, which is equivalent to an awful lot of car journeys or air miles. If all farmers around the world were to farm in a similar manner, there is the potential to offset all the global carbon emissions created by global transport, which is about 30% of the carbon dioxide emitted. Or another way of looking at it, by increasing soil organic matter content from 1.7% to 5.2% on agricultural land globally, would take 1 trillion tons (0.9 trillion tonnes) of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, bringing it down to pre-industrial levels.

The good news is that we are not the only people practicing some fantastic sustainable farming techniques growing quality crops, livestock and wildlife habitats on our farm. As well as pressing rapeseed grown on our farm, we buy seed off four other LEAF Marque farmers who are just as passionate as we are in the way they farm. So, between us we are all doing our bit to preserve and protect the planet for future generations.

Further reading, in no particular order:

Montgomery. D.A, 2017. Growing a Revolution, Bringing our soil back to life. (Available from Amazon here.)

www.indigoag.com/the-terraton-challenge

www.co2.myclimate.org/en/flight_calculators/new

www.soilquality.org.au/factsheets/organic-carbon

The environment has always been at the heart of everything we do, which is why LEAF (Linking Environment And Farming) is so important to us. As a LEAF Demonstration farm and LEAF Marque producer, we are so proud of the work the LEAF team do to encourage other farmers to take a more sustainable approach to their farms.

Here, Caroline Drummond, Chief Executive of LEAF (Linking Environment And Farming) talks about early beginnings, driving forward more sustainable farming and connecting communities…

Our Roots

LEAF celebrates its 30th anniversary next year. We began life in 1991 with a tiny office at the Royal Agricultural Society of England (RASE) at Stoneleigh Park, Warwickshire and one very ancient computer! Initially set up as a three-year project, with seed funding for only three years, we had to become self-financing. And we did just that! The focus in those early days was to set up a national network of LEAF Demonstration Farms – to showcase sustainable farming in action. We launched five farms in that first year and created a membership offer that farmers could sign up to.

LEAF was set up to do two things: to promote sustainable farming through Integrated Crop Management (ICM) which, as more livestock farmers came on board, later became Integrated Farm Management (IFM) and secondly, to raise public awareness of what farmers were doing to farm with environmental care. LEAF has grown to become a global leader in delivering more sustainable farming and those two objectives remain as true today as they did then.

Sustainable Farming Through IFM

Consumers increasingly want to know more about what they feed their families; they want to eat healthily; they want to know where their food has come from and how it was produced; they want assurance of its sustainable credentials. As people started to visit our growing network of Demonstration Farms, they were asking where they could buy food they were seeing bring grown. This heralded the beginnings of LEAF Marque – our environmental assurance system.

Today we work in 27 countries with over 900 LEAF Marque certified businesses worldwide and over 40% of UK grown fruit and vegetables is grown on LEAF Marque farms. Farrington’s Mellow Yellow were one of the early trailblazers as both a LEAF Demonstration Farm and one of the earliest adopters of LEAF Marque – the first rapeseed oil to be LEAF Marque certified!

We are hugely proud to have worked with the Farrington’s team over so many years. Their commitment to LEAF and all we stand for, has recently been demonstrated with them becoming the world’s first carbon and plastic neutral food brand.

Building Connections

People have always been at the heart of LEAF’s vision of a world that is farming, eating and living sustainably. Building knowledge and understanding of sustainable farming helps highlight the connections between all living things – soil, plants, animals and people. This understanding gives rise to an attitude of responsibility and care. As a LEAF Demonstration Farm and LEAF Open Farm Sunday host farmer, Farrington’s Mellow Yellow welcomes people from all walks of life to experience farming first hand. Bringing people closer to farming and how their food is produced is opening people’s eyes to the importance of sustainable farming and, in turn, encouraging them to make more sustainable food choices.

The way forward

Reflecting over nearly three decades, LEAF has come a long way! We haven’t achieved this growth alone. There is no magic bullet to optimising sustainable food production. It requires collective efforts of farmers, governments, retailers, NGO’s, scientists and individuals. All of us working together to achieve shared outcomes – more productive soils, cleaner water and air, greater biodiversity, efficient energy use and improved connections with people, farming and the natural world.

The partnerships LEAF has built over its nearly 30-year history will be key as we navigate the next critical few years.

Oils

Oils Rapeseed Oil

Rapeseed Oil Chili Oil

Chili Oil Dressings

Dressings Blackberry Vinaigrette

Blackberry Vinaigrette Classic Vinaigrette

Classic Vinaigrette Balsamic Dressing

Balsamic Dressing Honey & Mustard

Honey & Mustard Ultimate Chilli Dressing

Ultimate Chilli Dressing